Stranded On Santa Cruz

I was so ready to come out to California and recharge my battery. The following people live in California:

- Mark Zuckerberg

- Kobe Bryant (part-time)

- Some migrant workers in the Central Valley

- My best friend Doug and my cousins Greg, Leah, Lauren, Kevin, Fran, Marvin, Allen, and Marilyn

Doug and I always have a blast together. Over four years at Vanderbilt, we learned we could live with each other; after a month in Europe, we learned we could tolerate each other in isolation and speak honestly when one of us is being an annoying shit. If that’s not best friend criteria, then no one has best friends and we’re all just muddling around like microbes in the primordial soup.

Our time together did not disappoint. One night, we bought a drink for Cuba Gooding Jr. and subsequently got him to write the word “VAGINA” on a piece of paper before spending four hours with the three prettiest girls in James’ Bar at Venice Beach.

But the highlight of this trip was always going to be camping in Channel Islands National Park with my cousin Greg.

I’ve looked up to Greg for as long as I can remember. At first it was the age factor; he’s two and a half years my senior, and he filled the void of older brother in my life, which of course meant that I took after him in as many ways as possible. I have a particularly vivid memory of him making my sister’s Barbie and Ken dolls make out in their Barbie car, giving me my first taste of sex ed. Man, that was fascinating to watch.

We played water polo together for one season in high school, when he was the senior captain and I was the immensely awkward freshman who needed to learn how groups of boys operate. But it was after that our relationship really matured. You see, Greg, unbeknownst to me, had suffered from depression for years. After he graduated high school, he turned increasingly to substances as medication, diving deeper and deeper into the black hole of addiction. I didn’t learn all the horrible details until I interviewed Greg about his ordeals for a project during my junior year at Vanderbilt—all I knew was that he had moved to Los Angeles for treatment in a group home and that, against all odds, he had become a success story. He has been sober and completely drug-free since October of 2009.

Seeing my cousin emerge from his life-threatening struggle and witnessing the way he now conducts himself added a vast new dimension to my respect for him. I look at Greg and see someone who is incredibly comfortable in his own skin, confidently going about life exuding joie de vivre because he’s been to low points that I can’t even fathom. In his words, he’s found serenity, and that shines through him at all times. Spending a couple days with him taking in the breathtaking vistas on Santa Cruz Island was going to be an amazing opportunity for me to bask in that light and hopefully absorb some, not to mention getting some quality time with a cousin who’s usually separated from me by two thousand miles.

I didn’t really anticipate that things would get more interesting than that, but I guess anyone who goes camping and closes their mind off to that possibility isn’t really in search of an adventure.

The first thing to realize about the Channel Islands is that they’re islands. It’s easy to take islands for granted when you fly there—as I’ve done to Hawaii, Aruba, and Barbados—but there’s actually a whole bunch of ocean separating them from the mainland, and that ocean can be rough on boats and marine equipment, especially during an El Niño winter. A few days before we embarked, Greg and I got an email telling us that the pier on Santa Cruz island had been damaged by waves and we would be disembarking from our ferry via dinghy, the way old-timey sailors landed on new continents or American soldiers landed at Normandy (minus heavy gunfire). To me, that sounded pretty badass. Then we actually hit the ocean and the massive swells that rocked our vessel gave my stomach reason to question my bravado. It felt like we were on a roller coaster, which is awesome for two minutes at a time but really starts to wear on you after an hour and a half of pitching, yawing, and rolling. Fortunately, unlike some peons on the lower deck, Greg and I managed to hold our breakfasts down.

By the time we reached Santa Cruz’s Scorpion Anchorage, where we’d be kayaking and camping, it was already 12:30 pm—two hours later than we had expected to arrive. With the ferry departing at three and our kayaks expected to be onboard, we had about two hours to explore the myriad caves and cliffs along the island’s rugged coast. We felt horrible for the day trippers who would barely have any time to do anything. Word to the wise: if you ever go to the Channel Islands, the only way to make the trip worthwhile is to camp for a night.

If anything, the sea conditions had intensified since we landed, but we had paid a handsome fee to rent the kayaks. There was no way we were going to completely bail. So Greg and I put on our swim trunks, zipped rain jackets on over layers of insulation, and took to the ocean. We hoped that the jackets would at least keep us somewhat dry. Unfortunately, they only really work when you don’t submerge yourself completely in the water. Within the first minute of our voyage, I had already violated that rule with the least graceful attempt at mounting a kayak in world history. It took Greg a good while longer, but after about a half hour of paddling into a merciless headwind he was broadsided by a wave and tumbled into the Pacific. With him went his phone.

Having achieved the holy trifecta of outdoors misery (cold, wet, tired), we struggled back to Scorpion. Greg pulled his comatose iPhone from the pocket he had hoped was waterproof and told me not to mention anything about it so as not to unleash his fury. “This didn’t happen,” he said. “What didn’t happen?” I replied. He stared at me. I winked.

Luckily, we still had some dry clothes, so we changed into them and trudged up the road to our campsite, nestled in a eucalyptus grove surrounded by these beautiful, desolate hills. On our way, we saw the park ranger, Casey, driving toward us in an NPS white pickup. As he reached us, he stopped and rolled down his window.

“How’s it going, gentlemen?” Casey asked us.

“We were silly to go kayaking,” Greg responded. Casey laughed.

“Well, I just wanted to let you guys know a couple things. First of all, they’re saying that the wind is gonna be pretty rough tomorrow, so they might not be able to get a boat out here to pick you guys up.”

“What?”

“Yeah, if the wind’s blowing in the wrong direction they’ll have ten foot swells in the harbor. They’ll probably at least send a boat out here to tell you what’s going on, they have a bullhorn they can use to talk to you. But if it doesn’t happen tomorrow, it’ll definitely happen Wednesday. You guys wanna stay on the island?”

Greg and I looked at each other and shrugged. We hadn’t come all this way for a couple disgusting, soaked hours of kayaking and the death of Greg’s phone. “Yeah, we’ll stay.”

“The other thing is that I’m leaving the island to go spend the holidays with my girlfriend in Beverly Hills. The other ranger should be here tomorrow, but tonight, there’s not going to be a ranger on the island. I’ve left operating instructions on the radio in the ranger station, and there’s a satellite phone up there too.”

Wait, really?

“You fellas have a good stay on the island!” And Ranger Casey drove off.

Really? He couldn’t have waited to be relieved by the other ranger? First he freaked the shit out of me by saying that a couple weeks ago a girl had her quad severed by a boulder that fell on her kayak. Now he was abandoning us on a windswept, barren island that felt like a bastardized combination of St. Andrew’s and Akira Kurosawa’s Ran? I was getting that Into Thin Air feeling, where dangerous factors slowly but surely pile up and lead to inevitable disaster.

Sure enough, the next morning, we find out that there’s not going to be a boat. In fact, there might not be a boat until Sunday. I have a flight home on Friday. Greg has a flight on Saturday. This is unacceptable. Was this risk in the fine print of the waiver we signed at Island Packers? Probably. But who reads the fine print? Not even future law school students read the fine print.

We’d packed up our tent in the faint hope that we would be headed home on time, and we weren’t about to set it up again. That would’ve been too depressing. Instead, we headed up to the ranger station with the thirteen other survivors. No ranger? No problem. We walked right in, set up shop in the several bunkhouses comprising the compound, and raided the kitchen because there was no way we weren’t going to eat the unopened chunky peanut butter in the pantry when we had barely packed enough food for two days.

Did we play things up a little bit? As much as possible. We were stranded, yes, but there’s a difference between actually being stranded and merely having a wrench thrown in your plans. The following amenities were available to us at the ranger station:

- A radio and a satellite phone

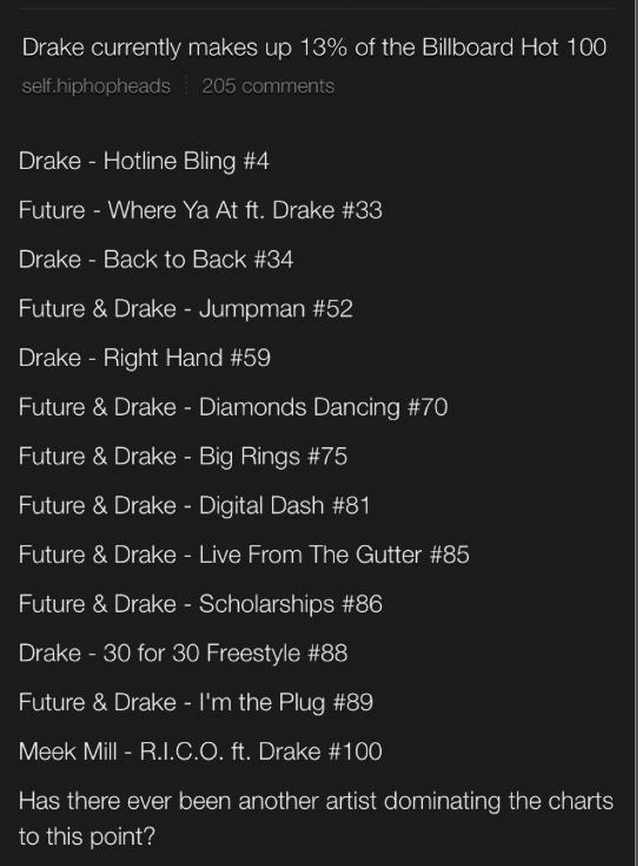

- Free wifi to live tweet the situation and convince our families that we weren’t going to die

- Leather recliners in front of a TV equipped with a VCR/DVD combo player and DISH

- A selection of movies including Learning Morse Code, Eye Injuries, and The Princess Diaries

- Trivial Pursuit, the 1981 version (the only version?)

We decided to take our chances with DISH at first and ended up with Men In Black II, which ended up mostly playing in the background as we got to know our fellow strandees and my dad sent me obnoxious iMessages comparing each person to an analogue on Gilligan’s Island. There was a middle-aged brother and sister from Alaska with the sister’s 17-year-old son, who was wearing a sleeping bag-coat hybrid; there were a thirty-something brother and sister with their spouses; there were a Mormon father and son who had packed coolers of food to sustain their hyper-vegan diet (no processed or frozen foods, no oils, no fun); there were three girls in their mid-late 20s who had to change their flights; and there was a lone wolf from Boston who took on the role of grizzled, helpful survival vet. A negative Nancy could’ve ruined the vibe, a single annoying douche could’ve made our stay on Santa Cruz a living hell…but fortunately, everyone got along perfectly well. Pro tip: if you’re ever stranded on an island, eat the negative Nancies and annoying douches first, so that your group becomes harmonious and in touch with the chi.

Fast forward through MIIB, the most recent Indiana Jones movie and our third backpackers’ meal (they were all surprisingly delicious, though context helped), and a group of us is playing Trivial Pursuit on the floor because we were in a living room and you stay up later if you have a living room. Had we still been in a tent, we almost certainly would’ve gone to bed shortly after sunset, like humans used to do (and probably still should). Instead, we were struggling through a hobnob of arcane cultural references and oddly specific questions. “What happened eighteen minutes past five in the evening on November 9th, 1965?” I don’t know, some old man in Queens farted and his underwear got a little dirty? No, turns out “the lights went out.”

At one point, the game was openly mocking us. The question posed to me: “What part of Britain did the Nazis occupy during WWII?” None, I answered. Churchill defended his island, no matter what the cost. Of course, that wasn’t the answer.

“The Channel Islands.”

A big ol’ FUCK YOU from Santa Cruz to all of us.

Greg went next and hit on a geography question, which I asked him. “What consists of Jersey, Guernsey, Alderney, and Sark?” I had to stifle my laughter in my arm, because I knew what the answer was even before looking at the reverse side of the card. Greg didn’t, so I told him.

“The Channel Islands.”

I don’t believe in fate or a higher power, but if I did, this sure as hell would’ve been a sign.

It really wasn’t worth it to continue after that. So we all went to bed and listened to the wind try to blow our cabins down all night, as if the Big Bad Wolf had mastered circular breathing.

The next morning, we radioed into land and found out a boat was braving eleven-foot swells to come get us. It did feel pretty badass to tiptoe across the damaged pier, the ocean visible at spots below it, to board our vessel, and watching dolphins jump our wake as we slogged back across the Santa Barbara Channel gave me a sense of almost cartoonish blessedness. It was too perfect…this had all been too easy. Greg and I “rewarded ourselves” with probably two thousand calories each at The Habit Burger in Ventura, but for what? For sitting around in a cozy living room and acting like we were hardcore pioneers?

It’s been about a week since my return to the mainland, and if there’s anything I learned from my faux-harrowing encounter, it’s that it’s so easy to make a much bigger deal out of things than they deserve. Sometimes it’s fun, like when you’re making-believe that you’re some real-life LOST crew and you’ll be needing to fight off The Others and a smoke monster. But other times, like when college students allow legitimate gripes with their campuses to become all-consuming and self-destructive, it becomes clear that our tendency to catastrophize setbacks probably isn’t the most helpful thing in the world. Exaggerating after the fact for a good story is one thing; exaggerating during the events that comprise the eventual story is another.

Just like probably anyone reading this, I’ve had a few disappointments over the past month. A Kickstarter for a webseries I was trying to produce failed to reach its fundraising goal. I was supposed to see a screenplay I co-wrote made into a film this week, but the director had to leave the project. And I’ve wasted a ton of time overall, wiling away hours on sports website comment sections and the dark bowels of YouTube when I could have been writing or consuming more rewarding pop culture. But they’re all just small bumps in a road that will certainly have its share of peaks and valleys before it inevitably plunges into eternal darkness. Freaking out about them won’t solve anything, and in fact will get in the way of my ability to experience life as it happens.

Besides, it’s hard to think of anything as a huge deal when I have a cousin who’s locked in the daily battle of serious addiction recovery.

With that in mind, my New Year’s Resolution is to take things in stride. That isn’t to say that nothing’s a big deal, or that a stoic perspective is the way to navigate through an inherently meaningless universe…rather, it’s about managing your freakouts, spending your emotional capital on the right things, and always keeping in mind the story you’ll tell about the present. It’s the sort of lifestyle that keeps your battery fully charged at all times.